Understanding Vitreous Detachment: Causes, Symptoms, and Care

Read time: 7 minutes

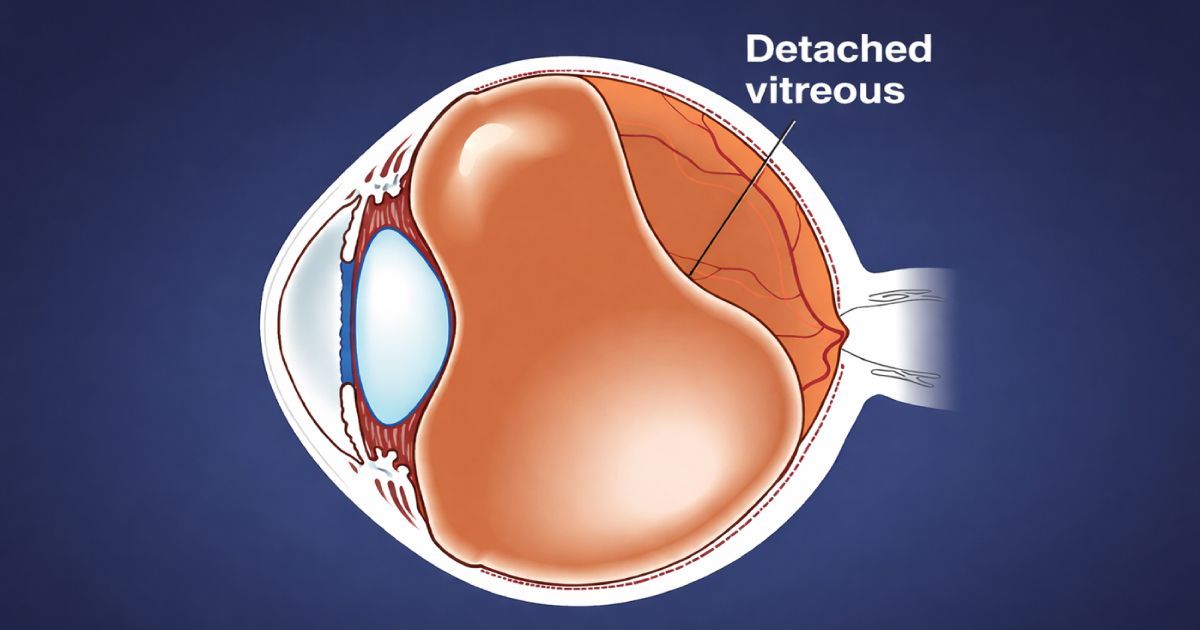

Our eyes are remarkably complex, each a small, self-contained world of tissue, fluid, and light. Among the most delicate parts of that world is the vitreous humor—a clear, gel-like substance that fills the space between the lens and the retina. Over time, natural changes occur within this structure, and one of the most common - and often alarming - of these is called a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD).

Although vitreous detachment can sound serious, it’s often a normal part of aging. Still, because it shares early symptoms with more dangerous retinal conditions, understanding what it is, why it happens, and what to watch for is essential to protecting long-term vision.

According to the [National Eye Institute (NEI), posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is a common, age-related change in the eye’s gel-like interior that can cause floaters or light flashes but is usually harmless.

A Brief Historical and Scientific Perspective

The vitreous body has fascinated anatomists for centuries. As early as the 17th century, scholars like Johann Gottfried Zinn documented the clear “glass-like” material within the eye - hence the term vitreous, from the Latin vitrum, meaning glass. For much of history, it was thought to be static and inert. It wasn’t until the 20th century, with advances in ophthalmic imaging and surgery, that scientists began to appreciate its dynamic role in maintaining eye structure and retinal health.

By the 1970s and 1980s, improvements in slit-lamp biomicroscopy and optical coherence tomography (OCT) allowed clinicians to observe how the vitreous separates from the retina with age. These insights helped distinguish posterior vitreous detachment, a natural, age-related process, from more serious retinal tears or detachments.

Today, OCT and high-resolution retinal photography give doctors an unparalleled ability to detect vitreous changes early and track their progression safely.

What Is the Vitreous Humor?

The vitreous humor fills about two-thirds of the eye’s volume, forming a transparent cushion between the lens and the retina. In youth, this gel is clear, firm, and composed primarily of water (about 98%), along with collagen fibers and hyaluronic acid which are key components that help maintain its shape and transparency.

The vitreous is not attached to the retina across its entire surface, but it adheres more firmly at certain points around the optic nerve head, the macula, and the vitreous base near the front of the retina. These attachment points are where detachment events begin.

Over time, the gel undergoes syneresis, or liquefaction. As collagen fibers clump together, the vitreous becomes less uniform. Eventually, the outer portion of the gel can separate from the retina and collapse inward toward the center of the eye—creating what’s known as a posterior vitreous detachment.

Causes and Risk Factors

The primary cause of vitreous detachment is age-related degeneration. By the time most people reach their 50s or 60s, the vitreous naturally begins to liquefy and shrink.

The American Society of Retina Specialists (ASRS), explains that PVD typically develops as part of the natural aging process but can occur earlier in people who are highly myopic, have undergone eye surgery, or experienced eye trauma.

Additional factors that may accelerate vitreous detachment include:

- Gender: Slightly more common in women, possibly due to hormonal changes affecting collagen.

- Eye surgery or trauma: Cataract procedures or injury can hasten vitreous separation.

- Inflammation (uveitis): Chronic inflammation can alter vitreous structure.

- Genetic predisposition: Some individuals have weaker vitreoretinal adhesion, leading to early-onset PVD.

While vitreous detachment is often benign, these risk factors can influence how and when it occurs.

Recognizing the Symptoms

For many, the first signs of vitreous detachment appear suddenly and can be unsettling. The most common symptoms include floaters and flashes of light.

Floaters appear as small dots, cobwebs, or translucent strands drifting across the visual field. They are shadows cast on the retina by clumps of collagen within the liquefied vitreous.

Flashes (photopsia) occur when the detaching vitreous tugs on the retina, stimulating it mechanically. These may look like flickers, streaks, or bursts of light, usually in peripheral vision.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) notes that while most floaters and flashes are caused by normal vitreous changes, a sudden shower of floaters or persistent flashing lights can signal a retinal tear or detachment and should be evaluated immediately.

Symptoms typically ease over several weeks as the vitreous stabilizes. However, because similar signs can indicate retinal problems, prompt examination by an eye doctor is always recommended.

Diagnostic Evaluation

When vitreous detachment is suspected, your Urban Optiks eyecare professional performs a comprehensive dilated eye exam. Using specialized lenses and lights, they can visualize the vitreous and retina directly to confirm whether a posterior detachment has occurred.

Modern tools such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and ultrasound imaging produce cross-sectional views of the retina and vitreous, helping detect subtle traction or tears that may not be visible during a standard exam.

The main diagnostic goal is to differentiate benign PVD from retinal tears or detachments. If a tear is found, immediate treatment with laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy can prevent permanent vision loss.

The Course of Vitreous Detachment

Once the vitreous separates, it typically remains detached permanently. In most cases, this process is harmless and completes over several weeks or months. The brain gradually adapts, filtering out floaters and restoring a sense of visual normalcy.

Occasionally, complications such as retinal tears, vitreous hemorrhage, or epiretinal membrane formation can occur. Eye doctors usually schedule a follow-up exam within 4–6 weeks after a new PVD diagnosis to ensure no delayed retinal damage develops.

Management and Treatment

There is no medication or direct treatment required for uncomplicated PVD. The best approach is monitoring, reassurance, and awareness. Most floaters become less noticeable over time as they drift away from the line of sight.

Patients should, however, remain alert for changes. A sudden increase in floaters, new flashes of light, or a dark curtain over part of the vision could signal a retinal tear and should be evaluated urgently.

In rare cases where floaters severely impair vision, vitrectomy surgery may be performed to remove the cloudy vitreous gel and replace it with a clear fluid. Because it carries risks such as infection, cataract, or retinal damage, this surgery is reserved for exceptional cases.

Advances in Understanding and Future Directions

The study of vitreous detachment continues to evolve. Modern imaging technologies such as swept-source OCT allow clinicians to visualize the vitreoretinal interface in microscopic detail, identifying early traction points before symptoms arise.

Studies have highlighted how these technologies are reshaping understanding of vitreous structure, improving early detection, and refining treatment approaches for associated retinal complications.

Research is also exploring pharmacologic vitreolysis — the use of enzymes to safely induce controlled vitreous separation in certain retinal conditions. Meanwhile, public education has improved dramatically: patients now understand that many new floaters are harmless, but that any sudden visual changes still warrant prompt evaluation.

Living With Vitreous Detachment

For most individuals, vitreous detachment is simply another milestone in the natural aging of the eye. Once the process stabilizes, the risk of complications decreases significantly. Maintaining regular comprehensive eye exams helps ensure long-term retinal health.

The American Optometric Association (AOA), in addition to your eyecare professional, advises patients experiencing new floaters or flashes to schedule a dilated eye exam as soon as possible to rule out retinal complications—and to continue routine checkups for ongoing monitoring.

With good awareness and care, most people adjust well to these visual changes and continue to enjoy clear, comfortable vision.

The Takeaway

A posterior vitreous detachment is one of the most common age-related changes in the eye. While the sudden appearance of floaters or flashes can be unsettling, PVD is usually harmless and self-resolving. The key is vigilance: understanding symptoms, seeking prompt evaluation when changes occur, and maintaining regular eye care.

With today’s advanced imaging technology and highly trained clinicians, vitreous detachment can be diagnosed and monitored safely—preserving both sight and peace of mind as the eyes evolve naturally over time.

Share this blog post on social or with a friend:

The information provided in this article is intended for general knowledge and educational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice. It is strongly recommended to consult with an eye care professional for personalized recommendations and guidance regarding your individual needs and eye health concerns.

All of Urban Optiks Optometry's blog posts and articles contain information carefully curated from openly sourced materials available in the public domain. We strive to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the information provided. For a comprehensive understanding of our practices and to read our full disclosure statement, please click here.